Destination: Canada

live at Koerner Hall, Toronto, June 2, 2017

Toronto has been crowned the most diverse city in the world, so it’s fitting that it’s now home to the most diverse musical group: the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, 12 musicians from around the world who are collaborating to compose pieces that draw inspiration from their musical roots.

“The great thing about living in Toronto and Canada is that … there are great virtuoso musicians from pretty much anywhere in the world,” says Mervon Mehta, who conceived the idea for this orchestra. He’s also the executive director of performing arts at the Royal Conservatory of Music. “I said to myself, what if we figured out a way to bring all of them together and create a new sound that kind of looks and sounds like Toronto in 2017?”

-

Padideh Ahrarnejad

Iran

-

Sasha Boychouk

Ukraine

-

Alyssa

Delbaere-SawchukCanada — Métis

-

Luis Deniz

Cuba

-

Anwar Khurshid

Pakistan

-

Lasso

(Salif Sanou)Burkina Faso

-

Paco Luviano

Mexico

-

Aline Morales

Brazil

-

Demetrios Petsalakis

Greece

-

Matias Recharte

Peru

-

Dorjee Tsering

Tibet

-

Dora Wang

China

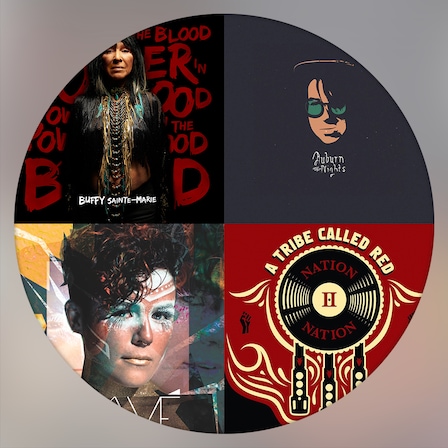

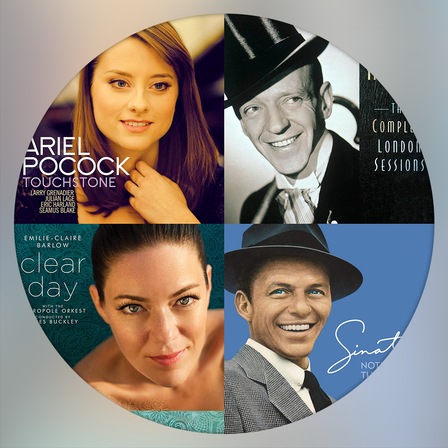

More than 125 people from 47 different countries auditioned to be part of Mehta’s project. Only twelve made the final cut. The New Canadian Global Music Orchestra includes Padideh Ahrarnejad (Iran), Sasha Boychouk (Ukraine), Alyssa Delbaere-Sawchuk (Canada – Métis), Luis Deniz (Cuba), Anwar Khurshid (Pakistan), Lasso (a.k.a. Salif Sanou) (Burkina Faso), Paco Luviano (Mexico), Aline Morales (Brazil), Demetrios Petsalakis (Greece), Matias Recharte (Peru), Dorjee Tsering (Tibet), and Dora Wang (China). Juno Award-winning trumpeter, composer and bandleader David Buchbinder was brought on to oversee the artistic direction.

David Buchbinder addresses the ensemble during a performance at CBC in Toronto.

Photos by Cathy Irving

Working with musicians from so many different musical traditions was a big draw for the 12 members. But for one, there was an added motivation: the significance of Tibet being one of the 12 countries listed in the orchestra. Born in exile in India to Tibetan refugees, Tsering has dedicated his life to learning and sharing traditional Tibetan music and dance. Even though he has never visited his homeland, the Chinese government’s presence in Tibet and its impact on Tibetan culture weighs deeply on him.

“This is not just for me personally,” Tsering says. “I feel I have to work hard because I’m representative of Tibetan communities. So it’s very important.”

“We’re not trying to take a trip around the world. We’re trying to take all of the world and morph it into a new Toronto sound,” assures Mehta. “Hopefully, the end result, which we will all hear, is that these tunes are from all over the world but they can only actually have completion here with these musicians in Toronto, today in 2017.”

To read a Q&A with each member of the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, keep scrolling.

Padideh Ahrarnejad

Instrument: tar

Composed by Padideh Ahrarnejad

Arranged by David Buchbinder

Destination: Canada

Origin

Iran

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Padideh is the newest of the new Canadians, and is a breath of life and light in this ensemble.”

Padideh Ahrarnejad was named the best tar player several times at the Fajr Music Festival, one of Iran’s most prestigious music festivals, founded in 1986. She started learning music when she was 12. A tar soloist from Tehran, Ahrarnejad immigrated to Canada in July 2016 with her husband, two children and her parents.

“When we moved to Canada, we wanted to have the first year to learn English,” says Ahrarnejad. But music quickly took over. “[There are] so many Iranian communities — we had so many concerts there.”

A graduate of the Tehran Conservatory of Music, Ahrarnejad has trained under some of Iran’s most acclaimed musicians, played around the world and been a member of both Iran’s Radio and Television Orchestra and the country’s National Music Orchestra.

Since relocating, Ahrarnejad has played with Toronto-based musician Pedram Khavarzamini, one of the world’s foremost Iranian Tombak players, and is now part of the Iranian Modal Music Ensemble of Toronto.

Q. Why did you decide to move to Canada?

I wanted to have stability for my music, for my life and I wanted to live in peace because we have so much trouble in Iran. It’s very good here. I like Toronto because we have so many cultures and it’s the best for my music because I have the opportunity to play with other musicians from around the world. But in Iran we don’t have the chance to do that. I have a family. I have two children. One of our goals was to have a peaceful life. Q. Why did you want to be part of this orchestra? Were you apprehensive about anything? When I was living in Iran, I always had this goal that I want to play with other musicians from other countries. This was the best for me because I saw so many people from other countries and I could learn the music from them. When I first wanted to join this project, I was worried about my English. In the beginning, for five or six sessions, we didn’t play together. We only talked and there were some practice [exercises]. After that when we started to play, we didn’t have any charts. In Iran we always had charts for our music. We had notes. But here we didn’t have anything. It was very complicated. But now I get it and we have some music and we’ve found out how we can play together. Q. How has this project connected you to your roots and Canada? It’s very good for me and all of the Iranians here that I can show our instrument, and our culture to other people. I’m proud of that. I think being in this orchestra has helped me become familiar with Canadian people, Canadian culture and everything that’s related to Canada. My English got better. This orchestra helped very much because I always have the Iranian community around me but here I can speak to other people. Immigrants have so many problems: they miss their family; they miss everything they had before. But this orchestra helped me in not thinking about that. I was happy. To watch Ahrarnejad perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Sasha Boychouk

Instruments: woodwinds and ethnic Ukrainian flutes

Composed and arranged by Sasha Boychouk

Destination: Canada

Origin

Ukraine

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Sasha is one of the most versatile musicians. He can play anything and read everything.”

From co-founding the Winnipeg Jazz Orchestra to playing with artists such as Gladys Knight and the Pips, Michael Bolton and Michael Bublé to performing on numerous Broadway productions in Toronto, Sasha Boychouk has had a long and varied musical career.

Born in Ukraine to a musical family, Boychouk studied at the illustrious St. Petersburg Conservatory. His focus shifted to jazz after graduating, when he became a member of the St. Petersburg TV/Radio Orchestra. Later, Boychouk would move to Moscow and become leader of the Moscow Sax Quintet, where he was playing in 1991 when he moved to Canada.

Boychouk settled in Winnipeg, and his musical career took off instantly. “Winnipeg has a great musical community. Very tight but at the same time very wide in traditions and variety of styles,” he says. “There was a saxophone quartet ready to go and I was accepted as a part of it and involved in many projects in Winnipeg. I was lucky from day number two and started to play music.”

After years of performing in Winnipeg, a friend approached Boychouk about going on the road for a couple of gigs. “I tasted that life, being on the road. And I decided to be closer to the hubs for that kind of environment,” he says. So in 2004, he moved to Toronto permanently.

Q. Do you remember your journey to Canada and what motivated you to make it your home?

It was Sheremetyevo Airport in Moscow. We flew out and at that time the airport was surrounded by tanks because we almost expected to have a Gorbachev coup. Surprisingly our plane flew away and we were really relieved. We arrived in Montreal and flew to Winnipeg right away. We were greeted with a beautiful sunny day. I'll never forget the colours, the smells, the fresh air. It was something very special, very different from Moscow at the time. I was looking for freedom. Personal freedom. Creative freedom. That’s what it was and still is. Canada to me is freedom, prosperity, possibilities, future, support of each other, tolerance, freedom of expression.

Q. What drew you to this project? How has it been, playing with musicians with such different backgrounds, especially when everyone isn’t trained to read music?

Ethnic music is something I’ve carried with me from the early days of my childhood. That’s where I feel like I need to explore this. It’s about time I do something for myself. It’s not for money, it’s not for fun music, it’s not for good music. It’s just something for myself. I may be a little bit selfish here but I want to play my instrument, which I didn’t play for maybe 30-40 years. I opened my case, I opened my Ukrainian flutes and started to explore them again and see if I still remember something. That’s probably the reason. Also experimenting — this is a good way to experiment.

I prefer traditional musicians not to read music. I prefer sometimes, just to have really raw music coming out of somebody. All of them are amazing musicians and when I listen to them, it’s like “Wow!” It’s like the Earth, something growing out of it without any polishing. It’s just perfect. Like a perfect flower. That’s what really attracts me. I just love it.

Q. How has this project connected you to your roots and Canada?

Why didn’t I stay in the States … I wanted to do it many times. It’s a bigger country, lots of opportunities. But I chose Canada. Canada to me is like a mosaic. It’s not a melting pot. They always call the States a melting pot. I don’t like melting pots. I like mosaics. From a little distance you see a picture, but if you come closer you can pinpoint — here’s this culture, here’s that culture. They stay together but at the same time they keep their roots. That’s what I like. I’m heavily involved in my Ukrainian community, playing in Ukrainian projects and dances. I love it. But at the same time I know that next door there’s another gig and it’ll be somebody from Africa, celebrating their life. And we live side by side and we cross over sometimes, like in this project.

To watch Boychouk perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Alyssa

Delbaere-Sawchuk

Instruments: violin, viola, jaw harp, spoons and vocals

Composed by Alyssa Delbaere-Sawchuk

Arranged by David Buchbinder

Destination: Canada

Origin

Canada — Métis

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Alyssa is so versatile and fearless. She can play Arcadian fiddle tunes in the middle of an African jam, and can make it fit in.”

Alyssa Delbaere-Sawchuk’s foray into music began at age three, when her parents bought her a violin. Born in Winnipeg, she and her three younger brothers all trained in the Suzuki method, an approach developed by Japanese violinist Shinichi Suzuki. After numerous years of training in purely classical music, Delbaere-Sawchuk was eager to learn other types of music. She joined the children’s group 40 Fiddling Fanatics when she was about seven or eight.

“I later on became more and more interested in my Métis ancestry. That became a big part of my musical development as well,” says Delbaere-Sawchuk. Her ancestry goes back to the Red River Colony, a historical Métis community just outside Winnipeg.

Delbaere-Sawchuk’s family moved to Toronto in 1997 when she was 11. There, she and her siblings met world-renowned fiddler Anne Lederman at a string camp and later discovered that she lived around the corner from them. “[Lederman] became our go-to person for the development of our folk music and Métis music repertoire,” she recalls.

What started with that violin so many years ago turned into a full-blown passion. From the Royal Conservatory in Toronto to the Lausanne Conservatory in Switzerland to an ongoing doctorate in classical and fiddle music traditions on the viola at the University of Montreal, Delbaere-Sawchuk continues to pursue a career in music.

She sought training outside of the classroom as well. Delbaere-Sawchuk was mentored by Ojibwe elder fiddler Lawrence “Teddy Boy” Houle and collaborated with his brother, James Flett, on an album that garnered an award in the best fiddle and best instrumental album category at the 2008 Canadian Aboriginal Music Awards. She also plays with her siblings in a band called the Métis Fiddler Quartet. Their album, North West Voyage, won the award for best traditional album at the 2012 Canadian Folk Music Awards.

Q. How was your audition? What were some of the things you had to do?

It was really wonderful. I felt like I was coming home because I spent 2001 ‘til 2005 at the conservatory almost every day of the week studying. It was like a homecoming for me. In fact, going and coming back to a place is part of my identity, if you will. “Teddy Boy” Houle, a fiddler that I worked with, gave me the name Nenookaasi or hummingbird in Ojibwa because of my interest of going into the past and bringing it into the future. But I can also relate that to other things such as having studied at the conservatory for many years and then returning later on and spending lots of time there. So I feel like I’m coming back home.

This was the most different audition that I’d ever done. I’ve done many classical auditions where I have to play by myself and there are specific pieces and I know exactly how they’re going to sound and how they should sound. It’s typically behind a curtain and this process was completely different because there was an element of teaching people, of playing with other people, of improvisation, not knowing what’s going to go on and who the other people are that you’re going to be playing with as well as just playing with instruments that I’d never played with before. I’d never played with tar. I’d never played with n’goni before.

I find it really interesting that there were four of us in that audition, and all four of us were accepted. There was sort of a magical moment of like, “Oh!” While we just happened to be put in this audition group together, and it just really worked. The other three were Paco [Luviano], Padideh [Ahrarnejad], and Salif [Sanou]. In the group, not only am I the only bowed instrument and the Canadian representative but I’m the only bilingual French and English member. So I am translating constantly for Salif, who doesn’t speak a lot of English and so it’s another skill that I guess I am developing, other than just learning other types of music. I’m developing my translating skills.

Q. As the musician representing Canada in a group called “New Canadian,” how do you feel about that name?

I think it’s a great thing. It’s a beautiful thing to celebrate diversity. The cities in Canada are very culturally diverse. So it’s great to be able to celebrate diversity through this cross-cultural exchange of music. It makes me feel quite happy and excited because I get to learn more about other cultures as well.

Q. If you had to describe this project to someone in one sentence, how would you describe it?

It’s a world music genre with many different identities. It’s not only celebrating and sharing those different identities but also figuring out creative ways of integrating different identities within the same piece without getting in the way of overstepping, so that it’s very much a shared space for cultural diversity.

To watch Delbaere-Sawchuk perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Luis Deniz

Instrument: saxophone

Composed by Luis Deniz

Arranged by Hilario Durán

Destination: Canada

Origin

Cuba

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Luis is a terrific improviser and brings a Latin flair to what we’re doing.”

Saxophonist Luis Deniz started learning music when he was 10. Originally from the Camagüey Province in Cuba, Deniz couldn’t pursue jazz music from the get-go.

“Even though Cuba produces a lot of people that play jazz, and some of them have gone to New York and had great careers, there’s no real jazz education in place. Everything is classical. So I studied classical and did that for nine years,” he explains.

Deniz moved to Canada in 2004 to expand his jazz career. “Being a jazz musician, if you live in North America, then your chances of being able to play with better players, and learn more from them are far greater than if you’re in the Caribbean or anywhere else,” he says. His first gig in Toronto was to play with Cuban jazz pianist Hilario Durán. The two have worked together ever since.

A full-time musician who also teaches at Humber College, Deniz won the Grand Prix du Jazz General Motors Award (Montreal Jazz Festival, David Virelles Quintet, 2006) and the Galaxie Rising Stars Award (Halifax Jazz Festival, Rich Brown’s Rinse the Algorithm, 2010) and has played all over Canada, the U.S., Europe, Australia and Japan.

Q. What motivated you to audition for the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra?

Every other player in this band comes from a completely different language background than me. The history of jazz has proven that the people that have taken [jazz] the furthest have been people who haven’t been afraid to get out of their comfort zone. Knowing and understanding the language of jazz but then getting out of it. You have people like John Coltrane and he went to India. You have people like Miles Davis and he went to Spain. That was the main reason why I wanted to join because I wanted to learn from all of these people that come from completely different backgrounds than mine.

And I wanted to take what they had and see how I could input that in what I already do. Sort of enrich my language, if you will, especially as an improviser. It already makes a difference not being an American playing jazz. Just being Cuban and coming from a completely different background, I try to study the music, respect the elders, and know where it comes from. I’m already a hybrid. I’m not from New Orleans. I just want to add more to that hybrid and make it a pile of more things that will at the end be distilled within the language of jazz.

Q. How has this project connected you to your roots?

I feel like this has made me think even further than Cuba. For example, dealing with Salif [Sanou], Matias [Recharte], and Aline [Morales], I’m thinking about more of an African connection. Placing Africa as the motherland culturally, in that sense of the music, and where we come from. Cause then you have Matias from Peru and they have the [influence] from Africa and you have Aline from Brazil and [the influence] is as huge as the one we have in Cuba. Seeing all this and using Salif [from Burkina Faso] as the point of departure, that’s the part that has been most interesting to me. Cuba is something that is always on my mind because I grew up there but the nature of my instrument — I don’t think about Cuba or in Cuban terminologies as much as some people think I would.

The nature of my instrument — it was first made famous in France and then in the U.S. Those are the two big schools that drive what the saxophone is today. I can play the saxophone from the Cuban point of view; like how I grew up, there are certain rhythmic things that I do. Even if I try to play the sax like Charlie Parker, it’s not going to happen. And I want that because that’s how it comes out. That’s who I am. But the nature of what I do and my instrument and the music that I play, I think has little to do directly with Cuba. If anything, I have been thinking more about what Africa has meant for all of us and what we’ve been able to create on top of what came from there.

Q. How has this project connected you to Canada?

This project is really the pure definition of what Canada is. When I was a kid and I would think about Canada — and I think this is true of many people in Cuba — I don’t think I ever knew that Canada was the multicultural place that it is. I always thought that it was just white, green-eyed people. After moving here, living here and having the chance to travel the world a bit with my music, I have never seen a level of integration with immigrants, new immigrants, older immigrants, not even in places like London or New York, as much as I’ve seen here. It’s such a natural thing here. It’s super interesting. It’s like the pure definition of what this place really means. So being a part of this is amazing.

To watch Deniz perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

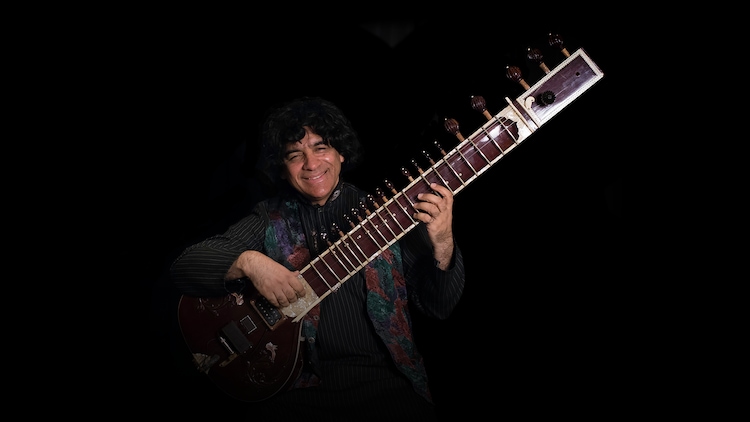

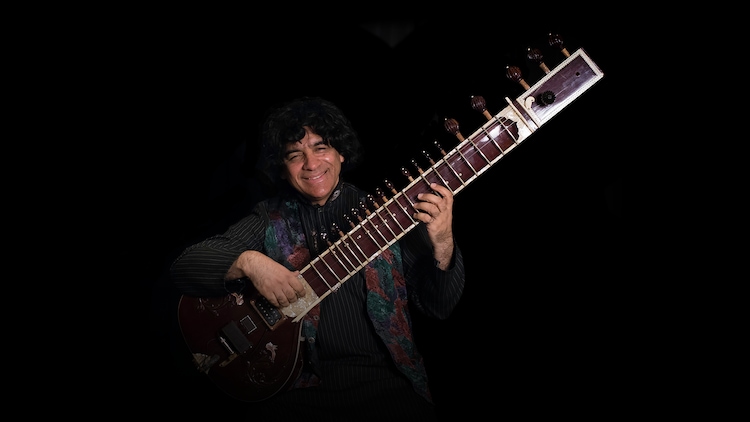

Anwar Khurshid

Instruments: sitar, flute, esraj, tabla, vocals and harmonium

“No Ma Ni (Missing Two Notes)”

Composed and arranged by Anwar Khurshid

Destination: Canada

Origin

Pakistan

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Anwar is the joker in the band. He always has a light touch to everything he does and says.”

From Life of Pi to Sultans of String, sitar player Anwar Khurshid has composed for and collaborated on numerous projects in the past two decades. Born in Quetta, Pakistan, he started learning music when he was four, and his decision to move to Canada was prompted by his brother.

“My brother was already here. At one point, he had come to Pakistan and I noticed how he had changed and how he had become a very thoughtful and considerate person,” recalls Khurshid. “Very practical and wanting to live life to its fullest and enjoying it. He had become totally different from what he was when he left for Canada. And I liked what Canada had done to him.” Lack of musical opportunities in Pakistan provided added motivation.

So in November 1989, Khurshid followed suit. He arrived in Toronto with two sitars and tablas in hand, wearing a large winter coat in anticipation of the infamous Canadian winters. And like many newcomers, he went through the rigamarole of working different jobs. Determined to not be caught in that cycle, Khurshid studied astrophysics and actuarial Science at the University of Waterloo and began working at Manulife. But he couldn’t stay away from the music, and quit his job to pursue it full time in 1999.

Since then, Khurshid has been the director of the Sitar School of Toronto, collaborated with musicians from different traditions, played sitar on film scores and composed his own music.

Q. How has this project reconnected you to your roots?

It’s very nice to see all these other musicians from all these other cultures and think of how they have developed their music in their own very intricate forms and compare it to my experience learning and doing music. That brings back all the memories of myself learning as I used to, and also realizing that actually a lot of music has its strength because it connects to the land that it comes from. There is definitely a great connection to the culture that that music brewed in. For me I would listen to Padideh's [Ahrarnejad] composition for instance and say, “Oh wow! This sounds like Raag Bhairavi, which is sung in the morning.” Or I would listen to Salif’s [Sanou] composition and to me it would be Raag Brindavani Sarang, which is often sung in the afternoon. Or I would listen to what Dora [Wang] plays and I would say, “Oh! This is very similar to the Raag Bhopali that I learned.” Demetri’s [Petsalakis] composition reminds me of Raag Kirwani. Paco's [Luviano] composition actually fits in our Raag Bhairav or Bhairo, which is also a maqam [a system of melodic modes] in Arabic music and a dastgah [musical modal system] in Persian music. So there are all these connections. The music itself is just a great connecting chain that connects us to our own background.

Q. How has this project connected you to Canada?

Well I’m Canadian and I don’t intend to be anything else anymore. And that’s how I identify myself, so whether or not this project was there, I would still call myself Canadian as I have been doing. But I think what it brings about is this strong sense that even though we all have our own backgrounds and we all have our own histories and we have our own cultures, but being here in Canada, when we get together for a rehearsal or a jam, we are actually recreating the cultural part, the melting pot so to speak, which reminds one of the bigger cultural melting pot that Canada actually is. It’s like a genius constructing an experiment and recreating it on a smaller scale to figure out how this melting process actually works and how this fusion actually happens and can we actually sound like good music, which is not music from our culture, history or experience but it is music that has been brought here, it has those influences but it is still Canadian music. It is music that we would not have created had we been living in our own countries.

Q. With so many musicians from so many musical backgrounds, what have been some of the challenges?

Certain instruments have strong challenges. Dorjee’s [Tsering] instrument might not retain its tuning. Tar, the Persian instrument that Padideh [Ahrarnejad] plays, can only be tuned to C. Same thing with the sitar. It can only be tuned to one key. During the performance there are so many strings that it cannot be tuned to something else. There are instruments like the oud, that can easily play certain forms of licks, which are melodic lines. But arpeggios might not work for some instruments. With sitar, it has a long neck. So to play “sa ga pa sa” [Khurshid says, singing] — that’s quite a bit of a jump. Four notes but you have covered the whole neck of the sitar. It’s very difficult to do that.

Because of the limitations of the instrument, people playing it learn to master certain things, enhance certain things, overcome certain difficulties and let certain difficulties go with their instruments. They practise very hard for hours and hours to make musical sense out of the limitations of their instruments. That’s an intellectual challenge. When you come and play with other instruments, how would you modify your instrument? How would you modify the tuning? How would you modify the phrasing that you play on your instrument?

The third thing is, even after you’ve done that, you try to figure out how you’re going to make things work. When you put it together, you need to have that sense that there’s something wrong with this phrase. It doesn’t sound good for some reason to my ears and how can I change that? That’s the third challenge in this orchestra — where you know even after you’ve done something you need to have the perception that it is good. After you’ve put it together, does the music actually sound like music?

To watch Khurshid perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Lasso

(Salif Sanou)

Instruments: fulani flute, kambélé n’goni, tamanin (talking drum), balafon, djembe, doum-doum and vocals

Composed and arranged by Lasso

Destination: Canada

Origin

Burkina Faso

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Lasso is so dynamic onstage. If we had a frontman, he’d be the frontman.”

Salif Sanou was born with music in his blood. Raised in a musical family in a small village in Burkina Faso, he moved to Canada in 2009. “My grandfather always told us that music will take you just about anywhere. You might not even know in which direction you’re going but the music knows where you’re going,” he recollects.

Growing up in an environment where people’s lives are deeply intertwined with music, Sanou started making music at six years old. Since moving to Canada, he has performed at the Montreal International Jazz Festival, FrancoFolies de Montreal, the Festival International Nuits d’Afrique de Montréal, the Vancouver Olympic Games and in the children’s play Baobab. His group Lasso & Sini-Kan (“Sini-Kan” means “the voice of tomorrow”), merges traditional African instruments with modern ones. Sanou sings and plays several traditional African instruments.

Q. Tell us about your foray into music. How did it all start?

I was born into a family of griots. In my country, griots are spokespeople. Griots play, talk, advise and find solutions. That is the role of griots. My grandfather and my great-great grandfather have always made music. They’ve always played and sang, played at baptisms, at funerals where they had to play for the king or play for the public. They also passed the message on to people, like TV or the newspaper. The griot is the one with the news; he is the one who has to distribute the news. So I was born into this family.

I started making music at the age of six, but in reality it was before I was even born. It was in my mother’s womb. My mother was a griotte who sang and danced up until my birth. I followed the same path. When I was born, I followed in my parents’ footsteps. I found myself in the dirt while the family played, even though I didn’t play. As a baby I would lie down next to the balafon [a wooden xylophone] and as they danced, the dust fell on me. But it wasn’t a problem. I was in the music.

Q. Did you have any formal training in music?

I never went to a teacher. My teacher was my family. Listening mainly. You must always be listening. Be very attentive. You listen, and watch very closely. And then your dad says to you, “It’s your turn; go play.” You have to accompany them, like the other person was doing. Sometimes, at home, when we would have nothing to do, we would take out the instruments and try to imitate our parents, from a very young age, thinking, “The last time when I was at a wedding, I saw my dad playing this song like this.” I always had the rhythms, the singing, the melodies in my head, and I would try to play them on the instrument. It’s a shame that in those days we didn’t have the technology to film or take pictures. I can only imagine. I would love to see myself as a young boy trying to play, but.

Q. Tell us about your first instrument.

The first instrument I owned was a djembe. A friend gave it to me. He saw me play and he said, “You play the djembe very well. I’d like to take classes with you.” So I gave him lessons. But when I gave him lessons I had to go borrow a djembe from my cousin. And my friend said, “You play so well, I’m going to give you a djembe. I’m going to buy you a djembe.” So he bought me a djembe. I was so proud of my first instrument. He paid me for the lessons, actually. This was truly a gift, a real gift.

To watch Lasso perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Paco Luviano

Instrument: bass

Composed by Paco Luviano

Arranged by Hilario Durán

Destination: Canada

Origin

Mexico

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Paco is the rock of the band.”

Bassist Paco Luviano was destined for music. Born in Acapulco, Mexico, he began recording with his father, acclaimed musician Macario Luviano, as a teenager. Paco moved to Canada 25 years ago.

“When I arrived in Canada, I did have some studies in music because of my dad but I never had formal studies in music,” recollects Paco. He ended up attending York University. “My life started changing after that because I was learning jazz. I was getting my [musical] reading skills in better shape. I was learning about music theory, which I didn’t really know enough when I first arrived in Canada. And that put me in a different position because I started doing a lot of Latin jazz and Brazilian music and other styles,” he says. He graduated in 2002.

Over the next decade-and-half, music has taken Paco around the world with such acclaimed artists as Hilario Durán, Jane Bunnett, Amanda Martinez, Patricia Cano, and the Shuffle Demons. From Liona Boyd’s Camino Latino to Stan Fromin’s Hutsul Project, a recording of distinct Hutsul Ukrainian songs, he has worked on numerous hybrid music projects.

Q. Can you talk about your musical background and why you chose the bass?

I come from a musical family. My father was a well-known musician in Acapulco, Mexico. We were three brothers and two sisters, and the three brothers all became musicians. We grew up in a house where there were all kinds of instruments and we used to use the room with the instruments as our playground. So I remember touching drums probably around when I was four years old. I started taking piano lessons at seven. I experienced a beautiful time in my life because I not only had access to all these instruments and my dad would teach us stuff but there were a lot of interesting musicians coming to my house to rehearse or to talk to my dad about music. And I had that experience, which sometimes you don’t have when you just learn music and go through school and come out of it. I had a lot of experience by listening to other people talk about music.

At one point my dad used to have dance bands playing Latin music, in the realm of salsa and Afro-Cuban-style music. In those days a lot of musicians were trying to get ahead and they would leave the city and new talent had to come up and start taking over those jobs. One day my father asked me if I wanted to learn bass because his bass player was moving out of the city, and I said yes. And that’s how I started playing bass. I didn’t necessarily pick that instrument up on my own. It was almost handed to me, and I had to figure out how to play it.

Q. What made you move to Canada?

Music made me come here. Originally I came here with a band performing popular North American music. They were originally a band from the U.S. and I knew the drummer because he used to be my dad’s student at some point back in Mexico. And all of a sudden I met him in Mexico. He asked me if I wanted to join his band. I was 23 at that time and I said yes. And I came to Toronto to perform with him for a year.

That band also played in the U.S. and I played with them there too, prior to landing in Toronto. I liked the Canadian life a lot, how people were treated in Canada, as immigrants. And I unfortunately saw a lot of things I didn’t agree with when I was travelling in the U.S. for a year. I was lucky to be a performer and just see things and not really experience them myself. But it was pretty sad to see how they would treat immigrants in the U.S., especially in small towns, because I used to perform in the Midwest. And even though at that point I was still assimilating with North American culture and my English was bad but what I saw — it was real.

Q. How does this project connect you to Canada?

There is something unique that happened in this country. The diversity that you experience in Toronto and Canada, you can sense that in the music, too. What you’re seeing right now in this project, it’s common. Not on this level but you have a Mexican guy playing with a Brazilian band; you have a guy that was born in Canada playing with a Cuban band in the city. So this crossing of cultures is pretty normal in Canada but it’s unique. And every time I travel, I feel that sometimes I take that for granted because we just feel like this is a norm and sadly enough we know it’s not when we travel out of Canada. But to have this vision, by Mervon Mehta — it’s just incredible. I strongly agree with him. This is what it feels like Canada is about. This multiculturalism, and integrity of different cultures, and working together. Even with the difficulties of having instruments that don’t really speak to each other that easily, we’re making it work as much as when we try to learn a language to communicate with somebody else. I put something on Facebook saying that this is made in Canada. This is what Canada is about. This is something that is very unique to this country.

To watch Luviano perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Aline Morales

Instruments: Brazilian percussion and vocals

“Iémanja (part II)” composed by Aline Morales, arranged by David Buchbinder

Destination: Canada

Origin

Brazil

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Aline is a beautiful singer, adding a Brazilian twist on Canadian music.”

With a background in capoeira and a Juno-nominated debut album, Aline Morales’s musical accomplishments are as multifaceted as they are eclectic. The Belo Horizonte, Brazil-born musician, who immigrated to Canada in 2005, is passionate about maracatu — an ancient carnival tradition rooted in the sugar plantations of Pernambuco, in northeastern Brazil, where slaves formed religious brotherhoods to preserve African culture and heritage. Maracatu was performed during the coronation of a slave king and queen.

Morales first began visiting Canada in 2002 and taught maracatu in Toronto. During those visits she created a community through her students, who ultimately helped Morales make the decision to settle in the city three years later. “Here in Canada, the way things went, I just felt good about it,” she reminisces. “I felt that something bigger was going to happen.”

Morales couldn’t have been more prophetic. Since immigrating here, her Brazilian drumming ensemble Maracatu Nunca Antes became a popular fixture in Toronto’s Kensington Market during Pedestrian Sundays. Her 30-member percussion troupe, Baque de Bamba, performed at countless outdoor festivals. She also became a resident artist at the Young Centre for Performing Arts, and appeared in one of Ontario Tourism’s “There’s No Place Like This” commercials. Most recently, the singer, percussionist and bandleader has been part of a trio that performs Forró music — another genre that has its roots in northeastern Brazil.

Q. Can you describe your musical background?

Music in Brazil is everywhere. It’s a social thing. I was actually old when I first decided to take music in my life professionally. And when I started to learn music, it wasn’t … you know people usually say, “Oh I started very young. I was seven.” I wasn’t. I was a teenager. I was 19 years old. Even though I loved music and was always around music — my dad is a big music lover — but I started first through this martial art capoeira. It’s a martial art that also has music involved. And I remember I practised for a long time — seven years — and at the end I would just be playing instruments and singing and not doing the physical part of it. That’s when I came across maracatu. That’s when I realized it was something that I was very into. I always did stuff in my life and I would drop it and not really take it very seriously. When maracatu came, I decided “Wow!” I’m good at it. I really like spending time doing it. And I just want to do this for the rest of my life.

Maracatu is a very old tradition that’s still alive in Brazil. It’s a tradition that comes from a coronation of an African king and queen. It started in the northeast of Brazil in the city called Recife. It comes from the slaves that were in Brazil a long time ago. And it still carries on. It’s very spiritual, very sacred. It’s beautiful.

Q. Do you remember your first gig in Canada?

When I came to Canada, I had in my mind that I’m going to work with maracuta and teach people this tradition. I was like, “How am I going to do that?” So I started looking for people who had an interest in Brazilian culture. I went to Samba Squad and started to promote maracatu and workshops. I had very few drums. In maracatu you need a lot of people, a lot of drums. At that time the internet wasn’t such a big thing. So I decided to do a little gig and invited a few musicians I knew, and friends. I set up this gig on College Street. And I did this very amateur show but so many people showed up, who were interested in Brazilian music and had never heard about maracatu. The gig was packed. I remember I announced that I was going to do a class at Christie Pits for free so people would have a taste of what it was. Over 20 people showed up and I did the class with very few drums and we rotated. People loved it. That’s how I started teaching drums and Brazilian culture here. Since that day I never stopped.

Q. What made you audition for this project?

This is a very ambitious, amazing and challenging project…. Putting a bunch of musicians from completely different traditions, when I think about it, I think in a Brazilian context. Musicians from different traditions — sometimes they are not necessarily musicians. We call them batuqueiros. They can play a certain style, do certain things but maybe it’ll be hard for them to do other stuff, to break through their traditions. And also the fact that you learn differently in different traditions. For example, I don’t read music. I have a completely different way of learning. I memorize, I’m good at listening. But I don’t read it. And I thought that could come across as well — different styles of learning. And I thought that it would be pretty amazing to be a part of a group of people like that. Different backgrounds, different styles, different languages — how will we bring that all together and make music? It could be a disaster but it could also be the most beautiful thing. Plus it had the Royal Conservatory name on it. It was a project they believed in. That’s why I decided to [apply].

To watch Morales perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Demetrios Petsalakis

Instruments: oud, guitar, lyra, bouzouki, riq and Greek baglama

Composed and arranged by Demetrios Petsalakis

Destination: Canada

Origin

Greece

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Demetrios is very steeped in Greek and Middle Eastern traditions.”

Athens-born, Toronto-based musician Demetrios Petsalakis says that he has “an instrument problem.” It’s an apt description when you learn that he began playing the bouzouki, a traditional Greek instrument, when he was eight. He then proceeded to learn the oud, guitar, lyra, riq and Greek baglama down the line.

Petsalakis moved to Canada in 2005 to study music at York University. “By the end of my years there, I started studying classical Arabic music with Bassam Bishara. Not at York University. Outside of the university environment,” says Petsalakis.

From the Ottoman era to Greek music from the ‘20s and ‘30s, Petsalakis’s taste in music is just as varied as the instruments he plays. “It depends on what I’m working on and when you catch me; especially being in Toronto, you’re exposed to a lot of different kinds of artists. And that intrigues your interest,” he says. “So if I happen to be working with someone from, say Pakistan or India, I like to go into their world and start listening to what they do and what their influences are.”

Performing with people from different backgrounds is an integral part of Petsalakis’s work as a musician. He has played with eight different bands in Toronto, in a variety of styles, with a focus on Greek and Middle Eastern lutes.

Q. What drew you to the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra and excites you the most?

It’s a very interesting concept of putting together a lot of these kind of musicians. I work in similar environments all the time but we never had the chance to have this much focus on the work. It usually takes a lot of time to build things together because we’re all working. But the environment here gives us the opportunity to work on things with a specific focus and get places faster. It brings all this great talent together in one group, which I enjoy.

The music is coming together and that’s very exciting. It’s awesome to hear all the backgrounds of the players. You can learn from them and we are learning a lot and moving forward. There’s so much information that the learning process is never going to end. We’re just going to build up on it. It’s one of the biggest things I enjoy about music, that there’s so much to learn that you can never even get close to it. The culture that you come from is one thing. But every individual player has their own idea of what their music is. So even that specific understanding where everybody is coming from — it’s a lot of fun.

Q. How has being a part of this orchestra connected you to your roots?

I have definitely enjoyed trying to put elements of my background into the music that I write and what I’m playing with other people. So it’s interesting to see what these elements are. Like how do you ornament a melody? How do you play it? Because of where you’re from, you tend to do specific things and you try to bring that in without being intrusive and taking away from the character of what someone else is doing. You’re playing, say Aline’s [Morales] tune, which is from Brazil, and I want to play oud on it. I want to bring some of my character in without intruding on her style. In order to do that I really have to reach into the essence of what I think Greek music is. What’s the essence of it and how can I bring that in while still making sense musically? It’s an interesting experiment.

Q. How do you feel about the name “New Canadian”?

I haven’t thought about it too much to be honest. I did move here and I’m also relatively young. But I’ve been here for a while now. So the term “New Canadian” is someone that I guess moved here compared to someone that always lived here. The good thing about Toronto and why I enjoy living in Toronto is that you don’t feel like a new Canadian because people are from all over the world. People are welcoming. When you go out, you don’t feel like you’re foreign. You feel like you belong, right away. Nobody made me feel like an immigrant. I felt very welcome. Most of my friends were born here but had parents who moved here from somewhere else. They made me feel like I belonged here. They never made me feel like a new Canadian but I can see how that is what I am.

To watch Petsalakis perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Matias Recharte

Instruments: drums, percussion, cajón, conga and timbales

Composed and arranged by Matias Recharte

Destination: Canada

Origin

Peru

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Matias is one of the musical leaders. He is very quick to learn the groove, and teach it.”

Percussionist Matias Recharte built his first drum set out of cans and buckets when he was 11. Born in Lima, Peru, Recharte studied Afro-Peruvian and Afro-Cuban folkloric music growing up, and attended the Rotterdam Conservatorium in the Netherlands. He’s now in the midst of a doctorate in music education at the University of Toronto.

After a master’s in ethnomusicology at York University, Recharte’s decision to pursue a PhD arose from a frustration with how ethnomusicology focused too much on theory and writing, rather than the practical aspect of music.

“I’ve been involved with music education all my life. The first school I went to encouraged us to teach when we were very young. When I was 13 or 14, I started working as an assistant in the summers,” he explains. “I continued to be involved in teaching all my life. I find that a very satisfying thing to do, to teach music. I felt that by studying a PhD in music education, I could maybe learn more about the different debates around music education. There’s this practical aspect to it that could also be interesting.”

Since moving to Toronto in 2013, Recharte has performed at the Beaches Festival, played timbales with salsa bands at Toronto’s Lula Lounge and performed with a Peruvian orchestra that plays Peruvian Cumbia music at various events around the city.

Q. Every musician in this orchestra has been asked to compose something new. Can you take us through your composition and the inspirations behind it?

The idea of the composition process was that each of us would bring something that would represent our musical selves. we’re from different countries and each country is associated with a certain kind of music. But the truth is that in every country different kinds of music circulate all the time, right?

I grew up with all these different kinds of music but always listened to Peruvian music. And I always liked and have been curious about Andean music. Andean music is a very rich tradition; there are as many different styles as there are people or towns. And the musicians are constantly recreating their music, making it new and fresh, modernizing it, and constantly reshaping it. When I composed my melody, I thought, “How can I add to that work with this group of musicians specifically?” So I composed a melody that was trying to imitate a little bit the language of Andean music, especially the Andean violin, that has a very particular technique and sound. I mixed that with a Brazilian rhythm that I thought has an interesting rhythmic connection with Andean music, which is maracatu. I also chose that rhythm because Aline [Morales] is an amazing maracatu drummer and she knows that style very well. So I thought I'll compose it so that it will fit with maracatu and she can bring something extra to the composition.

When I was composing this piece, I was listening to Northern Cree and they are an Indigenous music group. When I found out about their music, I was really inspired and touched by it and felt really strongly about it. It reminded me a lot of Andean music as well. There’s some kind of resonance there, especially with a drum. So I tried to make my piece speak to that, too, which I think is interesting for this project, particularly because Indigenous music is the music that came up from the people in this land. The reason I heard about Northern Cree is because I heard this story that they had been nominated seven times at the Grammys and they were still pretty much unknown in Canada. Probably because they were nominated for the [best Native American music album category], which is a category that gets very little attention usually. That’s how I heard about them and their music really touched me. So I tried to talk to that a little bit as well from my perspective — of my love and limited understanding of Andean music [and its connection to Peru].

Q. How has this process connected you to your roots?

It made me think about, “How do I want to represent myself musically?” When you think about it, it’s obviously very complex. I grew up listening to reggae, Peruvian music, salsa, Latin American music and Cuban music. My musical self is complicated and it’s very diverse, even though it’s within one person. It made me think about what it means to be Peruvian in Canada because one of the dangers maybe of multiculturalism is that you can kind of get lost. How do you become a part of society without losing your history? Even though my composition is relatively simple and straightforward, I hope that if somebody listens to it they‘ll also hear, the complexity that’s behind it.

Q. For people who don’t know about it, how would you describe the sound of this orchestra?

It’s a kind of sound I’ve never heard before. Nobody I think has heard this kind of sound before simply because there are instruments that never get together in a group. Also because, not only are the instruments diverse and special but the musicians themselves have different music in their technique, their knowledge, their repertoire — in their minds and bodies, basically.

The fact that we are given this opportunity to not perform whatever somebody else thinks this should sound like, but to actually compose our own melodies and try to arrange it for the rest of the people and instruments, even though we know very little about most of them — just working through that, it’s very challenging but at the same time I think it has the potential to create new sounds. Each of the performers have deep roots in their own styles of music. And when we get together and we try to make it happen together, that’s something new.

To watch Recharte perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Dorjee Tsering

Instruments: dranyen, flute, piwang, yang chin (dulcimer) and traditional Tibetan vocals

“Tashi Delek (Blessings on Everyone - i.e. Namaste)” composed by Dorjee Tsering, arranged by David Buchbinder

Destination: Canada

Origin

Tibet

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Dorjee is a stalwart of the Tibetan community in Toronto. He is a terrific singer with a beautiful tenor voice.”

Born in exile in India, Dorjee Tsering has travelled around Europe and North America, sharing Tibetan culture and raising awareness about the plight of his people. When he came to Canada in 2011 to perform at the Kispiox Valley Music Festival in B.C., Tsering decided to make it his new home.

“I was born in India but feel myself in Tibet, my parents’ homeland,” Tsering told CBC’s Metro Morning in 2015. Tsering inherited his love of singing and traditional Tibetan music from his parents, especially his mother. He graduated from the Tibetan Institute for Performing Arts in Dharamsala, India, which was founded in 1959 by the Dalai Lama. At TIPA, he learned how to play traditional instruments such as the dranyen, flute, piwang and yang chin (dulcimer). He also learned Tibetan opera, and several styles of singing and dance.

Tsering is keen on sharing and preserving Tibetan musical heritage. But he also wants to adapt and grow these traditions with new sounds. In 2015, he released Năng (Tibetan for “home”) — his first East/West collaboration and debut Canadian album, produced by composer/producer Lou Natale. His second collaboration with Natale, Thank You Canada, was released in 2017 to celebrate Canada’s sesquicentennial.

Q. Tell us about the first instrument you played and how you learned it.

The first instrument I played was the flute. I don’t remember how old I was when I started but I remember I was maybe in fourth grade. When I was in school, they had very few flutes. It was hard to get a flute because the school wasn’t very developed and we were living in refugee camps. But some of the seniors [in school] had flutes and I heard them playing. I would ask them to play and listen. And then I taught myself. I would watch what they were playing and try it myself. Sometimes if I got a flute in the evening I would try to play. We used to have bunk beds and I slept in the lower bed. The bed had pillars and my hands would wrap around [one]. There would be no sound but my fingers would touch the spots on the pillar and I would play from imagination. But after that, the school’s music group chose me because I could play and then I got more chances to play and better instruction.

Q. When you came to perform in Canada, once the music festival was over, why did you decide to stay on? How did you end up in Toronto?

I was playing on the West Coast. After my final concert, a friend of mine contacted one of the sponsors who had invited me. I had bought my return ticket. But we’re refugees in India. We have no citizenship even though I was born in India. So they talked and told me that if I stayed here, it would be a good opportunity. If I went back, in the future I would not get a visa and I would have to remain in India.

One reason why I decided to live in Canada was that in 2009 I got an invitation to Finland for a festival. I had no passport. I had a book called a yellow book — just an identity certificate. But they couldn’t put a visa on that. It’s like a travel document but it can’t be seen on the computer. I was in a lockup for two hours at the Finland border. Finally after many calls they [authorities] learned about the book.

I was reminded of that. I felt that if I was invited [to shows], it would be hard if I continued to live in India. We [Tsering, a friend and his sponsor in B.C.] had those discussions. I decided it was better to stay and get citizenship. I wanted to be Tibetan-Canadian. Therefore I decided to come to Toronto. It was a big city and had more opportunities to connect with many musicians.

Q. Why did you audition for the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra?

I love collaborative music. I love music that makes us feel like one. I love to exchange music. I am very happy to do this. The reason why I decided to stay in Toronto was because I wanted to meet many different musicians. Therefore, this is very important, more so than my other work. What the Royal Conservatory is doing is great and I respect it.

This isn’t just for me personally. The story of Tibet is very sad. I don’t want to say too much on the politics because I’m a musician. The one thing the Chinese government has tried to do is turn Tibetans into Chinese. They want to mix up Chinese songs and music style. So in this type of project, I can present pure traditional Tibetan music and I can show Tibetan instruments. In Tibet, they have tried to limit speaking Tibetan, writing Tibetan and singing Tibetan songs. They have imprisoned Tibetan musicians. The Chinese government is doing this. It’s not only for me personally; it helps and supports many Tibetan communities if I’m representing Tibet. I got many messages from my fans and our communities congratulating me.

To watch Tsering perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Dora Wang

Instruments: bamboo flute, flute, hulusi, xiao, panpipe and ocarina

Composed by Dora Wang

Arranged by David Buchbinder

Destination: Canada

Origin

China

Instruments

Jet Stream

Arrival

“Dora can pick up everything instantly.”

Dora Wang started learning the piano when she was five. Four years later, when her mother asked if she wanted to try another instrument, she seized the opportunity and began taking lessons on the Chinese bamboo flute, or dizi. Originally from Baoding, China, Wang joined the Tianjin Conservatory of Music in 1998 and studied there for 10 years.

“During these 10 years, I learned the bamboo flute — dizi — the xiao, the hulusi — some Chinese folk music instruments,” says Wang. “During this time I also had my group. A small orchestra, a female group. When I came to Canada, I also made a group — for females. There are four musicians and it’s called Melody of Bamboo Music.”

In her final year at the conservatory, Wang married her partner, who had been living in Canada since 2006. She joined him in Toronto in 2008 after graduating from the conservatory.

During Chinese New Year in 2015, Wang performed as a soloist at the Glenn Gould Studio. Most recently, she played the dizi on the score for Toronto-based filmmaker Philip Leung’s short film The Suitcase, about a girl hiding in a suitcase to get to Canada.

Q. What excites you most about being part of this orchestra?

When I play by myself, I only have one tone from beginning to end. In this group, I can hear lots of different tones. There are three musicians who play clarinet, piwang and sitar. They all play the flute. We have different flutes. Sometimes we play together and I think this is very good. I can try their styles; play both styles together. Secondly, we’ve played a song that Alyssa [Delbaere-Sawchuk] composed. When she does the first part and I come into the second part, I think my flute’s tone is very into this song. I’ve never had this style. I think we’re all very impressed and we all love it. That’s what makes me excited.

Q. What makes you nervous about this project?

Sometimes when we rehearse it’s very fun and there’s a chemical spark. Sometimes there are problems like the music customs, the keys, the rhythms. We have to figure it out. What makes me nervous is that in Chinese folk music we all play C, D, E, F, G, A, B flat — keys like that. In this group, some play C sharp or E flat or A flat. This is something I’ve never tried before. Maybe I’ve tried once or twice. I’m not very good at these keys. I had to change and at last I found a way. You know, a flute has two parts. I can pull a part out and lower it half a key. That’s how I figured it out.

Q. How has this project connected you to your roots, and also Canada?

We were asked to write songs. Our music must have some traditional characteristics. They asked us to do this so we could show different communities the music styles of different countries. I think that’s how it has connected us to our roots.

First of all, I have to say, I am really glad to be a part of this group, especially this year, during Canada’s 150th. I came to Canada nine years ago. In the beginning I heard a word — “multiculture.” I was wondering, “What is multiculture? Just that this community has a concert or performance?” And I’ve been thinking about this question for nine years. I think this group is really “multi-music.” Different countries came together to show audiences, we are all Canadians. We play Canadian music.

To watch Wang perform “Hymn to Freedom” with the New Canadian Global Music Orchestra, skip to the Encore.

Encore

The New Canadian Global Music Orchestra