The ’90s were one of the most transformative periods in modern Canadian music. Looking back, it feels like a time capsule, a period of such fervent musical growth across the country, with a distinct sound, look and feel.

Even if you don’t have a sense of nostalgia for Canadian ’90s music, there’s no denying the impact that decade had on generations of musicians to follow.

We’ve always had our singular big artists who find their way into the all-consuming American scene (e.g., Paul Anka, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Justin Bieber), but the ’90s were different. It wasn’t about one artist, but instead an entire scene across the country that produced more world-renowned superstars than any other era in Canadian music.

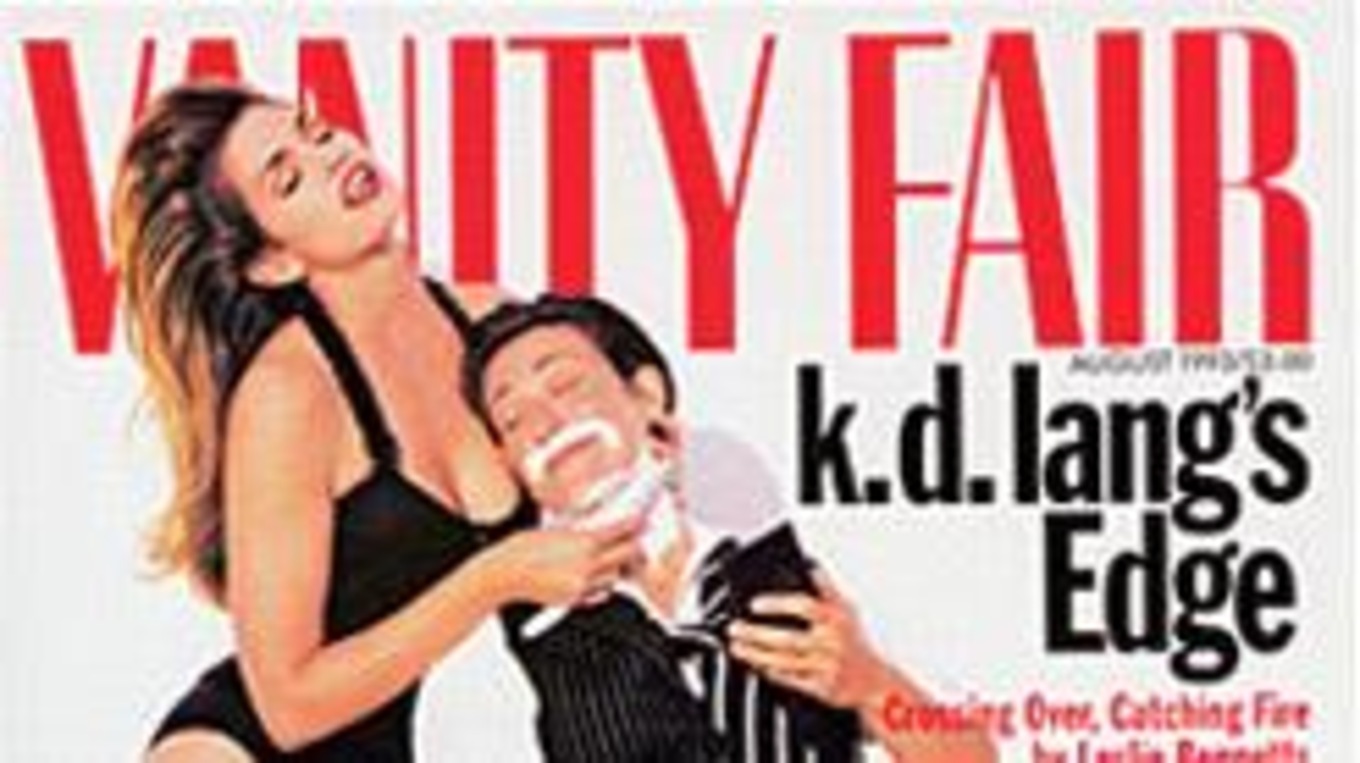

Both Celine Dion and Shania Twain became two of the most commercially successful musicians of all time. Bryan Adams and Tom Cochrane affirmed their status as the country’s biggest rock stars, while Sarah McLachlan was, simply put, ubiquitous. Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill went 16 times platinum and topped the Billboard charts, and between 1996 and 1999, she won nine Grammy Awards. K.d. lang’s “Constant Craving” won her the Grammy for female pop vocal of the year, and her appearance on the the cover of Vanity Fair with Cindy Crawford in 1993 instantly confirmed the Alberta-born lang as an international gay icon. Then there was Barenaked Ladies, who were at the forefront of one of the country’s most successful indie scenes (but more on that later).

Perhaps the most significant development in the ’90s was, in fact, the happenings outside of all the international acclaim, in the independent underground scene — out of which came BNL. In the mid- to late ’80s, a pool of homegrown talent had been simmering below the mainstream, and by the time the ’90s hit, it was a vibrant, frothing mass boiling over the edges. The underground became the mainstream, and the Cancon renaissance was in full swing.

“It was the fruition of all the groundwork that was laid in the ’80s, with punk rock, post-punk and new wave, and it was the moment people started to realize that an independent scene could actually exist in Canada,” says Jason Schneider, co-author of Have Not Been the Same: the CanRock Renaissance, which looks at Canadian music from 1985 to ’95.

For a generation of fans looking for new music, the ’90s were when it finally felt like Canada had caught up to the burgeoning underground scene in the United States. It became cool to know who the next big act was, and an industry quickly built up around that Canadian caché.

Cancon

A large reason behind the creative boom of the ’90s actually has to do with paperwork. The CRTC increased the amount of mandatory Canadian content on the airwaves from 25 per cent in 1971 to 30 in the ’80s, and 35 per cent in the ’90s. Radio was forced to play more Cancon, which meant more Cancon needed to be created.

In a Public Notice from 1995, the CRTC even noted the need for “a more streamlined approach to Canadian talent development,” and committed at least $1.8 million annually to radio stations in order to help with that development.

It was great news for shows like CBC’s Brave New Waves and stations like Toronto’s the Edge, which had already established themselves as outlets for burgeoning Canadian indie acts. For instance, Barenaked Ladies, Rheostatics and Sloan would all get their first major airplay from the Edge on their way to becoming some of the most beloved bands in Canadian music.

MuchMusic

The ’90s were also the golden age of music videos, with a young MuchMusic becoming the springboard for indie bands across the country.

Much was committed to growing homegrown talent, and beginning with their launch in 1984 the station played 10 per cent Canadian content, increasing to 30 per cent by 1987. It also channelled 2.4 per cent of its overall profits to Canadian bands in order to fund videos through what was known as MuchFACT (Foundation to Assist Canadian Talent).

“During the ’90s, our mandate was to assist bands that weren’t signed to the multinational labels,” says Bernie Finkelstein, co-founder of MuchFACT and founder of True North Records, noting that it was a distinct shift from previous practices. “When we started it in 1984, our acts were signed to multinationals, but in the ’90s we noticed there were a lot of artists doing their own things, so we were right there to support them.”

A good video being added to rotation on MuchMusic could make or break a band, as artists like Moist, Matthew Good, the Rascalz, Bran Van 3000 and Sloan could attest. It was the continuation of something that began even before the ’90s, encapsulated best with the Pursuit of Happiness, whose debut single, “I’m an Adult Now,” became a hit across the country based on a low-budget video that was added to rotation before the song was even released.

Pursuit of Happiness singer Moe Berg recounts when the band, upon returning to Toronto from a Canadian tour, arrived at a venue they were scheduled to play — and found it packed: “It was clear that they were all there to see us,” he said in Have Not Been the Same. “That’s when we realized this video meant something.”

Changing the indie rules

As low budget as “I’m an Adult Now” was, it was a small fortune compared to another video that launched one of the most successful Canadian indie bands of all time. Who can forget seeing a then-unknown BNL squeeze themselves into the tiny Speakers’ Corner booth in 1990 to perform “Be My Yoko Ono” on their way to becoming massive stars? Their DIY approach and massive success would change everything.

The Toronto band’s Yellow Tape, released in 1991, became the first indie release to go multi-platinum in Canada, proving that there was untapped talent in Canada’s indie scene. For the first time, the majors began aggressively chasing Canadian indie bands, rather than the other way around.

“There was a very competitive A&R situation in Canada in the ’90s,” says Kim Cooke, who worked in the A&R (artists and repertoire) division of Warner Music at the time, and is currently chair of nominating and voting for the Juno Awards. “It was an amazing time as a guy who was just getting into the A&R chair to see this stuff happening. It just seemed to be a spontaneous flowering of the indie scene. The Ladies and Moxy Fruvous came out of nowhere with platinum records, while the Waltons released Lik My Trakter independently before signing to Warner and driving it to gold. And one of my big signings was Great Big Sea, who had an incredible 20-year run.”

In fact, the success of Newfoundland’s Great Big Sea, including their 1995 multi-platinum major debut, Up, was proof that the labels were focusing their efforts across the country, rather than just in Toronto.

The Halifax Pop Explosion

Sloan, who were at the centre of the burgeoning ’90s Halifax music scene — later dubbed the Halifax Pop Explosion — was pursued and signed by Geffen Records (a.k.a. Nirvana’s label). The label considered Sloan the Canadian answer to Seattle’s superstars. Halifax became known as the Seattle of the north, based on the strength of Sloan and their contemporaries the Super Friendz, Thrush Hermit and Eric's Trip. The latter even released their 1993 debut, Love Tara, via Seattle’s highly influential Sub Pop Records, which briefly opened a Canadian office to service their Maritime acts like Hardship Post and Jale.

While Sloan are responsible for drawing attention to Halifax’s music scene, it was their approach to music in general that had a more lasting impact. For one, they were a democratic band, sharing songwriting between the four members, but they also had a vision — one that they stuck with. Following their famous battle with Geffen over creative control of their 1994 album, Twice Removed, Sloan would leave the major to release music on their own Murderecords, as well as the music of their Haligonian brethren.

It was a massive statement on behalf of musicians and independent labels across the country, from Mint and Nettwerk in Vancouver to Sonic Unyon in Hamilton, Ont., as well as indie labels started in the following decade, such as Arts & Crafts, Paper Bag, Light Organ and Constellation: be committed to local scenes from day one. A local act could make it without the machinations of a major American label, which is still one of the most significant developments to come out of Canadian music in the ’90s.