“Walk on, little Charlie

Walk on through the snow.

Heading down the railway line,

Trying to make it home.

Well, he's made it 40 miles,

Six hundred left to go.

It's a long old lonesome journey,

Shufflin' through the snow.”“Charlie Wenjack,” by Willie Dunn (1972)

Fifty years ago, a 12-year-old Ojibwa boy named Chanie Wenjack ran away from a residential school near Kenora, Ont., in an attempt to reunite with his family. It wasn’t uncommon for Indigenous children, forced to attend residential schools far from their families, to run away. In fact, nine others ran away from Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School that same day, all caught within 24 hours.

But Wenjack, whose father lived in Ogoki Post approximately 600 kilometres away, made it farther than the other children. His lifeless body was found, face up, beside the railway tracks on Oct. 22, 1966, a week after fleeing. He had succumbed to starvation and exposure. In his pocket was nothing but a little glass jar with seven wooden matches.

Chanie Wenjack, mispronounced as Charlie by his teachers, is the inspiration behind Gord Downie’s new multimedia project, Secret Path, which includes an album, a graphic novel by Jeff Lemire and an animated film. Downie, who sings in first-person on the album, from the perspective of Wenjack, was inspired, in part, by a Maclean’s magazine story his brother shared with him about Wenjack’s final moments, "The Lonely Death of Charlie Wenjack," published in 1967.

But in the 50 years since his death — and the 20 years since the last residential school was closed down — Wenjack’s tragedy has taken on a bigger meaning and inspired generations of Indigenous artists. This year alone, author Joseph Boyden has released a novella, Wenjack, told from the point of view of Wenjack, with a full-length novel, Seven Matches, to follow next year. He also wrote the Heritage Minute that told Wenjack's story and was released this summer. A Tribe Called Red also included interludes on the group's recent album, We Are the HalluciNation, which feature a narrator (also Boyden) addressing his lost brother, Charlie. But it all began with folk singer and politician Willie Dunn, who recorded the song “Charlie Wenjack” on his debut self-titled album in 1972.

“I feel like I’ve always known this story, ” says ShoShona Kish, from the folk-rock group Digging Roots. “It’s probably because of the song that Willie Dunn wrote about him. I grew up with his music. The stories he told were part of my education, musically, socially, culturally. It really came back into my consciousness when I spoke to Joseph Boyden about the project he was working on.”

Dunn was a close family friend of Kish's partner and bandmate, Raven Kanetakta, even teaching the aspiring musician to play guitar. When the imagineNative Festival asked Digging Roots to perform the song as part of its Oct. 22 event in Toronto commemorating Wenjack, A Night for Chanie, they didn’t hesitate. “Raven knew it already,” says Kish. “He knew it intimately.”

For Kish, the timing couldn’t be better for Wenjack’s story to swell up to the surface, as Canada still struggles to reconcile with generations of Indigenous families whose lives were ruined in an attempt at forced assimilation — a reconciliation that, you could argue, began with the inquest into Wenjack's death.

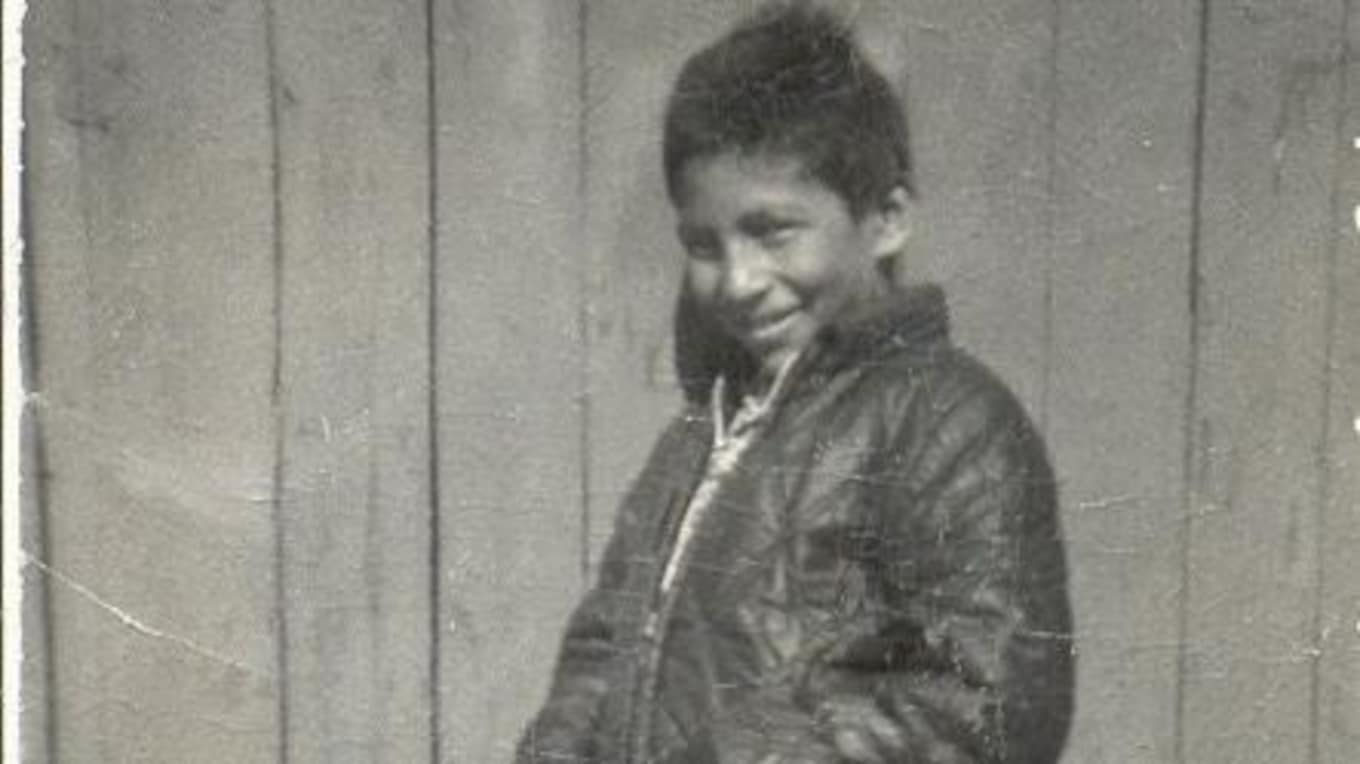

A family photo of Chanie "Charlie" Wenjack.

“It’s wonderful to have this story being told again,” Kish says. “It seems to be a really poignant moment to be talking about this moving and tragic story that distills the feelings we have around residential schools and the pain of that in our communities and the pain of those children. It’s really personal. It’s not just a statistic, he was just a little boy. His story tells so many stories. And this seems to be the moment that people are listening, which is a huge shift. I think it’s beautiful.”

Boyden and his novella, from which he will be reading as part of the Night for Chanie event, sits at the centre of this surge of creativity around Wenjack, a surge that still has several surprises to be released, aside from what’s already been announced. (Or so we’ve been told. Everyone interviewed for this piece was reluctant to reveal anything else).

“Indigenous children over seven generations were removed from their families in an attempted cultural genocide,” writes Boyden in the author’s note to Wenjack. “Chanie, for me and a number of others, has become a symbol not just of this tragedy but of the resilience of our First Nations, Inuit and Métis people — which is why I use the word ‘attempted.’ Our cultures were forced underground for a long time, but they have re-emerged despite the odds. And they are thriving once more.”

For A Tribe Called Red, it was exactly the piece the group needed on what was already turning into a very politically charged album. Working with Boyden, a friend of the band, also connected the members to Downie’s Secret Path, which in turn only added to the scope and magnitude of both projects.

“The connection was intentional, the joining factor there being Joseph,” says Ian “DJ NDN” Campeau, one-third of A Tribe Called Red. “He had pieces he wrote and was like, 'Hey I have this idea, Gord is doing this thing, is it cool if I wrote it like this?'”

“For Chanie Wenjack specifically, it comes at a time that we're discussing reconciliation for residential schools, and when Chanie was found in the '60s, that was the first time when Canadians were like, 'Wait a second, what's going on?'” adds Bear Witness, another third of ATCR. “It was the first big story. This kid died on the train tracks of exposure on his way trying to get home, so what’s going on that's so bad that a kid would go do that? People started looking into it. It took 30 years before they were all shut down, but I think that's why a lot of the conversation is coming about him specifically right now.”

It’s taken 50 years, but the story of Wenjack has finally elevated from the “family circle,” as Digging Roots’ Kish describes it, and into the consciousness of the millions of Canadians who heard Downie’s pleas during the moments of the Tragically Hip’s farewell show in Kingston to look North, to the people “we were trained our entire lives to ignore,” and to do something about it.

“It’s become something bigger,” says Kish. “It’s bigger than Chanie. This swell of creativity rising up to tell the story, it's on account of the swell of people willing to hear it, to come up and meet them. We’re opening our hearts.”

For Downie, who performed his first Secret Path show in Ottawa on Tuesday night, Wenjack’s story is “filling him up,” his brother told CBC.

Chanie’s sister, Pearl, and dozens of her family members even took the flight to Ottawa to attend the concert, the second of which takes place in Toronto on Oct. 21. The family has joined with Downie in an attempt at reconciliation, forming the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund, which focuses on creating relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. As part of that, Downie’s concert ended with him onstage, holding Pearl’s hand as she performed a traditional Anishinaabe healing song.

"My father died in 1987 without ever knowing why his son had to die," she told the crowd. "My mother still waits. To this day no one has told her why her son had to go." After a moment that was filled only with Pearl’s sobs, Downie stepped to the mic for a final word. “It’s just time to get started. It’s time to get going, OK?”

Proceeds from Secret Path, the album and illustrated book, will be donated to the Gord Downie Secret Path Fund for Truth and Reconciliation via the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba.

Follow Jesse Kinos-Goodin on Twitter: @JesseKG

Explore more

A history of residential schools in Canada

CBC Arts: Gord Downie's The Secret Path

5 things we learned from Gord Downie's interview with Peter Mansbridge

Enter a Tribe Called Red's HalluciNation

A Tribe Called Red have never been louder

23 indigenous musicians who are finally getting some long overdue recognition