In December 2016, when the all-women ensemble Pantayo took to the makeshift stage at a Toronto harbourfront café, the intrigue was palpable in the packed room. The Filipina-Canadian group was the grand finale of a secret Sofar Sounds concert. And when they brought in rack after rack of knobbed gongs in different sizes, it became evident why the host had pumped up the audience for something never seen before.

Christine Balmes, Eirene Cloma, Michelle Cruz, Kat Estacio, Katrina Estacio, Marianne Rellin and Joanna Delos Reyes make up the group. They play kulintang — a musical tradition found in Southern Philippines and neighbouring regions in South East Asia. Of the various indigenous communities with kulintang traditions, Pantayo's music focuses on that of the Maguindanaon and T’boli people, but with their own musical flare blended in. While descriptors like gong-chime, marimba and xylophone are all approximate, a video of an earlier 2016 performance paints a much more vivid picture of Pantayo’s music.

Pronounced “pan-TAH-yoh,” the name means “for us,” from the Tagalog root word “tayo” meaning “us” and the prefix “pan” or “for." It's borrowed from an intellectual movement, "Pantayong Pananaw" or "from-us-for-us perspective." Their music is nuanced and layered, much like the members themselves and their creative process. When CBC Music caught up with them at Cloma’s house, it quickly became apparent that from the name to the notes, exploring identity, acknowledging origins and composing conscientiously are integral to how Pantayo makes music.

With many subtle layers to peel back and as many voices to capture, we’ve honed in on seven things you need to know about Pantayo.

1. They were born out of a desire to explore kulintang

When Pantayo came to be in the winter of 2012, its five initial members — Balmes, Cruz, Estacio, Estacio and Rellin — had one thing in common: they were all born in the Philippines and had immigrated to Canada at various stages of their childhoods. All but Cruz had some exposure to kulintang instruments in school in the Philippines, where it’s used to teach music theory.

The five met through the Kapisanan Philippine Centre for Arts and Culture in Toronto and banding together came from a mutual desire to learn more about the kulintang instruments through self-taught workshops. But co-founders Balmes and Kat had first crossed paths in 2009 when Kat saw Balmes onstage playing kulintang instruments as part of the band Santa Guerilla. “That was when the first spark happened,” recalls Kat.

Balmes and Rellin couldn’t make it to this interview, but as Cruz recalls, “[Balmes] was talking to us all about creating this super, girl, gong group.” A year later Reyes joined while doing an arts mentorship at Kapisanan. She didn’t have any prior kulintang experience but, like everyone else, she too was born in the Philippines and immigrated to Canada at a young age. Cloma was the last member to join in 2015. Born and raised in north Vancouver to Filipino parents, she had done a kulintang workshop when she was young. She recalls seeing Pantayo for the first time at a conference and later came on board when she started working at Kapisanan.

2. Their music is better consumed when you know what kulintang is

“If we talk about the music, we have to talk about the context of where it came from,” says Kat, when asked to describe kulintang for newbies. The indigenous communities in the southern Philippines, where kulintang music originated, play the instrument for celebrations, ceremonies and as a part of everyday life, to unwind after a long day of work.

Instrumentally, Kat describes it as a series of pot gongs laid on a rack. A kulintang ensemble is made of different kinds of gongs: gandingan, agung and a single-headed drum called dabakan. “You know what always gets brought up is, 'Oh it’s like a gamelan from Indonesia,'” says Reyes. And while the two sets might be “cousins,” unlike gamelans, which are all standardized in their tuning, kulintang instruments are tuned to themselves, and each set varies from the next. For their ensemble, Pantayo also included the sarunay, which is a practice instrument for students before they play the kulintang.

L to R: Michelle Cruz on the agung, Kat Estacio on the gandingan, and Katrina Estacio on the kulintang. Performance collaboration with sculptor Tim Manalo. (Pantayo/DJ Tran)

The music, which gets passed down orally in these communities, is improvisational. And Pantayo’s track "Binalig" (meaning “made different”) embodies that very change in kulintang music. The members added kick drums and some synths once they finished learning the core (a.k.a. traditional) gong parts of the song.

3. They can’t be boxed into one genre

With seven members, who each play a variety of kulintang instruments, talking about their musical influences and identity can get unwieldy. What is their elevator pitch? How do they describe their music? These are two questions Pantayo frequently fields. “So far we have concluded that we are a punk group,” says Cruz tentatively. “Lo-fi gong pop punk,” adds Kat. “Gentle punk,” chimes in Cloma, as Cruz bursts out laughing. “And celestial R&B,” finishes Kat. They’re aware it’s not the most succinct elevator pitch, but it certainly provides them with direction as far as creating new material. “It started out as we would describe ourselves as a gong group,” says Kat. “But what does that mean?” So as their performances expanded beyond Filipino communities, so did their list of descriptors.

4. They are diasporic, not indigenous

“For us it’s important to note that our music is diasporic because we’re so far removed from the Philippines geographically,” says Kat. Equally important is acknowledging that they are appropriating something that is not theirs. “We don’t want to repeat the cycle of the colonized becoming the colonizers,” she explains. With an estimated 14-17 million indigenous peoples belonging to 110 ethno-linguistic groups, the Philippines is not a homogeneous nation. Layer that in with a history of colonization by Spain and an American occupation, and it becomes evident why Pantayo is so meticulous about attributing the group's music at the start of every performance. “I think using diasporic is something all of us can identify with. It also points to the other influences that we bring in,” adds Kat.

5. Their process of composing is thoughtful, collaborative and a work in progress

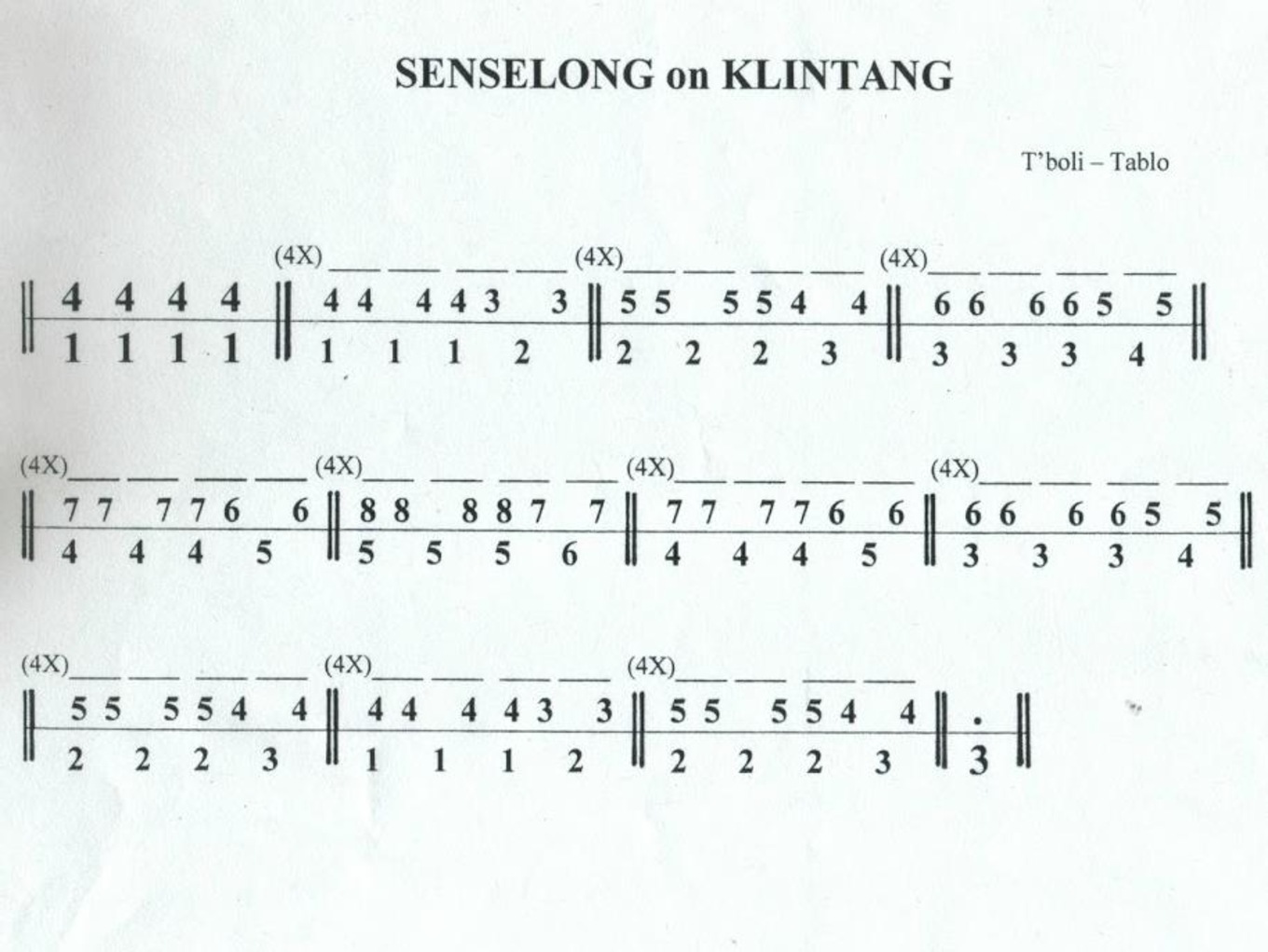

When composing, Pantayo’s jumping off point is kulintang sheet music they have access to because of studies and articles done by ethnomusicologists over several decades. But given that it’s improvisational, the contents of the sheet music are not set in stone. “When we started incorporating, synths, keyboards, drums and bass, that’s when we had to stop and think about what are the notes doing in this song particularly,” Kat explains when talking about songwriting. “How can we arrange it in a way that we’re not just taking one part and putting some hip-hop on top of it and calling it a fusion track?”

Sheet music showing the work of ethnomusicologists, that depicts how a track is laid out numerically on paper. Each number corresponds to a numbered kulintang gong. (Pantayo)

Now that they’re writing new material for the album, the group looks to Cloma and Reyes, who have more of a formal music background to guide the way.The overall process is part technical and part improvisational. Their track "Duyug" exemplifies these collaborative efforts. Cloma, who was the last member to join, added her own layer of interpretation. “I took what I felt was the groove of the song and added an appropriate baseline that was in key with the instruments,” she explains. That version of "Duyug" will be available on their album. In the meanwhile, here's what the first demo of the song sounds like.

6. They want their music to be played, not placed on a pedestal

Sheet music recorded by ethnomusicologists. Making sure the difference between diasporic and indigenous is understood. Acknowledging appropriation. With all the thought that goes into the music Pantayo composes, it’s easy to approach it with a sense of reverence. And that’s exactly what Pantayo hopes listeners won’t do.

“As a group, I don’t think we want people to consume it in a way that, this is so hype,” says Cruz. “Like, 'Oh wow, that’s gong music. It’s like nothing we’ve ever heard before.' That’s definitely something we want to stay away from.”

“I would want them to walk away and be like, ‘That’s a groovy song.’” says Katrina with a laugh. “Bobbing to it and moving to it, whichever way they are moved by it,” she adds.

7. They want their work to reshape how people think about music

“I do want people to enjoy the music but also for it to serve as a medium to open up conversations about Filipino-ness, the instruments, indigeneity. Also thinking about what are other ways Cancon, pop music, celestial R&B can look like,” says Cloma. “I just want folks to see that you can make music this way. You don’t have to follow a certain format. You don’t have to be confined to a certain genre. You just have to really make it your own.”

Equipped with a grant from the Ontario Arts Council, the group is now in the midst of working on its first album. In the meanwhile, for a taste of Pantayo’s beats, listen to its 2015 X Avant X performance at the Music Gallery.

Follow Tahiat Mahboob on Twitter: @TahiatMahboob

More to explore: