“The mists of history get thicker the further back you go,” says David Fallis, artistic director of the Toronto Consort, an early music collective whose next concert, entitled Illuminations, is a survey of music from the Middle Ages enhanced by projections of illuminations from medieval manuscripts. Performances take place March 2 and 3 at Trinity-St. Paul's Centre in Toronto.

Medieval music largely remains a mystery to classical music lovers, as though the mists of time Fallis refers to form an impenetrable barrier. But for those who perform it, the challenges and rewards are legion. When we spoke with Fallis recently, we began by asking him what it’s like to play music that’s more than 1,000 years old.

“You always have to face it with a certain humility — you don't, and you never really will know what it sounded like,” he told us. “That being said, you do look back at certain things and try to figure out how it might have worked, who played it and how fast — all the things you have to choose as a musician. We try to explore as much as we can, but at a certain point we just have to say, OK, this is how it's going to go. You just have to commit, and make it into an intriguing, inviting, communicative and emotional piece of music.”

Of course, Fallis and the Toronto Consort have decades of experience to guide them. The group was founded in 1972; Fallis himself joined as a singer in 1979 and has been artistic director for 27 years.

He agreed to provide us with an introduction.

What is medieval music?

"The medieval period began with the fall of the Roman Empire, around the fifth century, and ended with the Renaissance in Europe at the beginning of the 15th century," Fallis notes. “That's a huge length of time. Gregorian chant was the music of the Christian church. It was about the eighth or ninth century that it started getting written down and formalized. That's the earliest music that we'll perform.”

Why is there so much sacred medieval music?

“We see depictions [from the time] of people dancing or having a drink, and there's a musician in the background, so we know there was secular music-making, for sure,” reflects Fallis. “But it didn't get written down because this was all before the invention of the printing press. It actually was quite expensive to write anything down, and you had to be quite skilled. Most people couldn't read or write, so it was really only the wealthiest institutions that had that power.”

In the early Middle Ages, that meant the Catholic church and certain fortunate aristocrats.

“The other thing to say is that there was nothing like public education [at that time],” Fallis reminds us. “If you wanted to learn how to read, you had to go to a church school. If you wanted to become a musician you certainly had to go to a church-run institution. In terms of music-making, composers and musicians all got their training in church schools.”

How did they write music down?

If you were fortunate enough to be able to read and write, and you had access to the materials to do so, there was still no system in place in the eighth and ninth century for notating music.

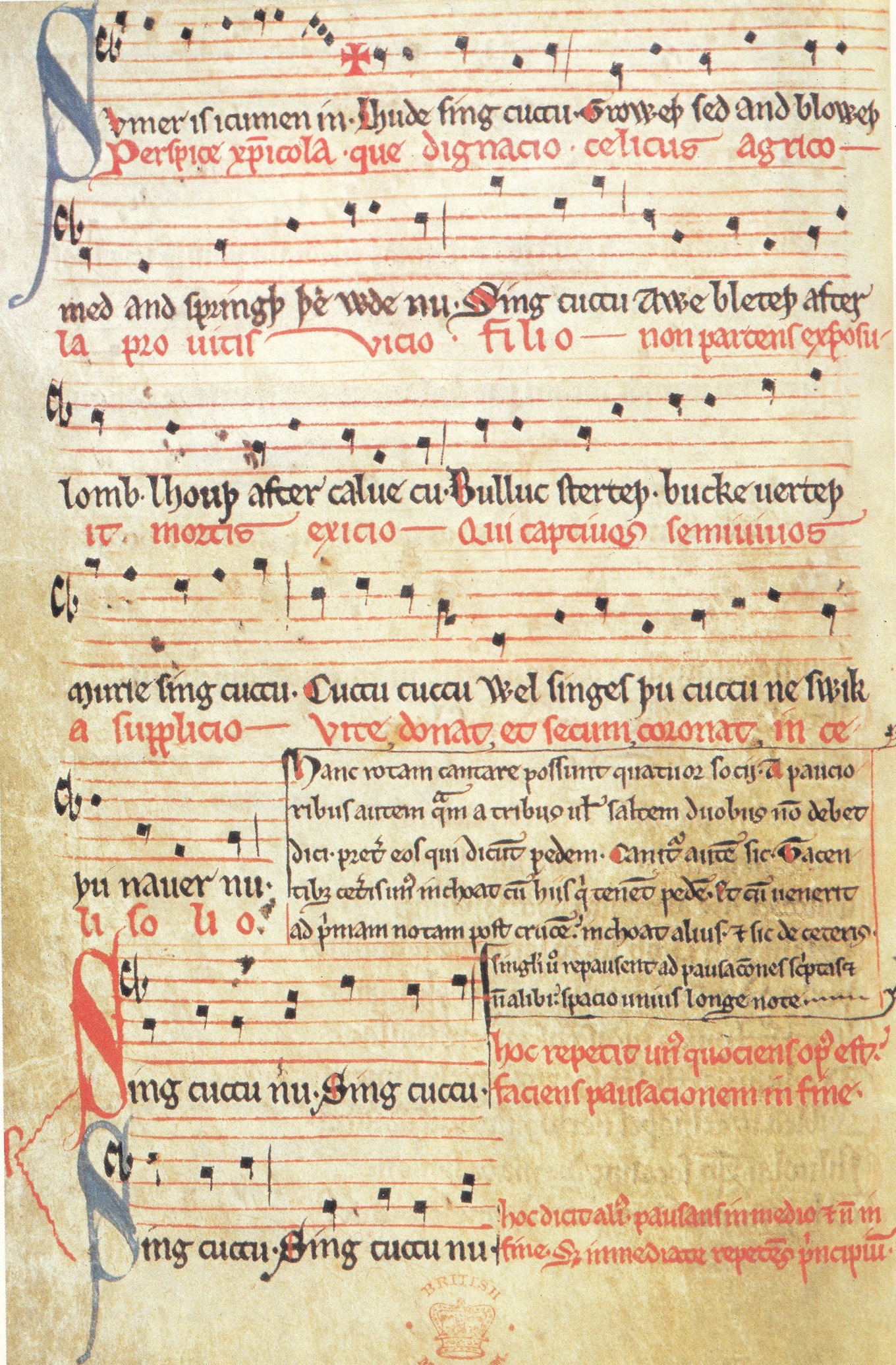

"Different kinds of notation evolved over this period, from the early neumes that are very hard to distinguish, to a kind of square notation that they developed," says Fallis. "A significant development is that of the staff: lines to show you how far your intervals need to go."

This original manuscript for the song 'Sumer is icumen in' shows early notation on a staff. (British Library, Harley MS 978)

"The notation of rhythm took a great deal longer because it's actually very tricky to notate rhythm, and so we don't really know how it went," he continues, pointing out that different modern editions of the same piece of music can give different-sounding results.

"Often the pitch sequence will be the same, but if you change the rhythm, it can make a difference to the feel of the song. It's a fascinating world and we do like to avail ourselves of the original notation. Even if you're not an expert, it will often tell you things about the music or about the text that you're interested in."

Fallis says Western music's emphasis on notation is a bit distinctive. "In lots of other traditions, you learn the repertoire by listening to your master, your teacher, your guru, and you do it over and over again until you get it in your ear, which actually is not a bad way of learning how to do music. That's what musicians are all about — developing their ear. Anyway, for better or for worse, Western musicians thought, 'I'd like to learn another person's piece, but I don't want to have to go and spend the time with the person, and if they write it down in a way that I can understand, that's quite useful.'"

What happened after Gregorian chant?

While the development of music notation was a major innovation of the medieval period, another was the creation of polyphony, or music in more than one part. "That's a path that Western music took and has never looked back," says Fallis.

"Suddenly you have two parts sounding and you have at least a two-part chord. And then three-part chords and four-part chords. And what you become interested in is the way things sound in chords, or what we call harmony, as opposed to the extremely sophisticated music from India, the Middle East and Africa, which by and large is not polyphonic. (They've developed, to be quite honest, often much more sophisticated rhythms than Western music has had [and] more melodic shapes.)

"So that's really why this period in Western music is so significant: because you get the first examples of polyphony. And you know, they allowed certain sounds to sound together that later would be considered dissonant. They were finding their way. It's a fascinating time."

What about secular music?

As mentioned above, less secular music from early medieval times has survived. But by the 12th and 13th centuries, music of the troubadours and trouvères did get written down. "A lot of these people were courtiers and they were kind of singer-songwriters as far as we can gather, and so we do have examples of that," notes Fallis.

The Toronto Consort enjoys delving into a 13th-century collection of Iberian songs called cantigas. "These are written in an old Portuguese language, and they're not secular in one way, because they're all about the Virgin Mary. [But] these songs would never have been sung in a church service. They're spiritual songs."

"There's [also] a very famous collection called the Carmina Burana, which are songs by wandering scholars," reflects Fallis. "The subject matter ranges all over the place: courtly love songs, erotic love songs, songs about springtime, or about how cold it is in winter time. They write songs about morality, songs about how some local priest is not following his vows, as though they're trying to reform the church [laughs]. It's an amazing collection and variety of styles and subject matter."

What can people expect at your Illuminations concert?

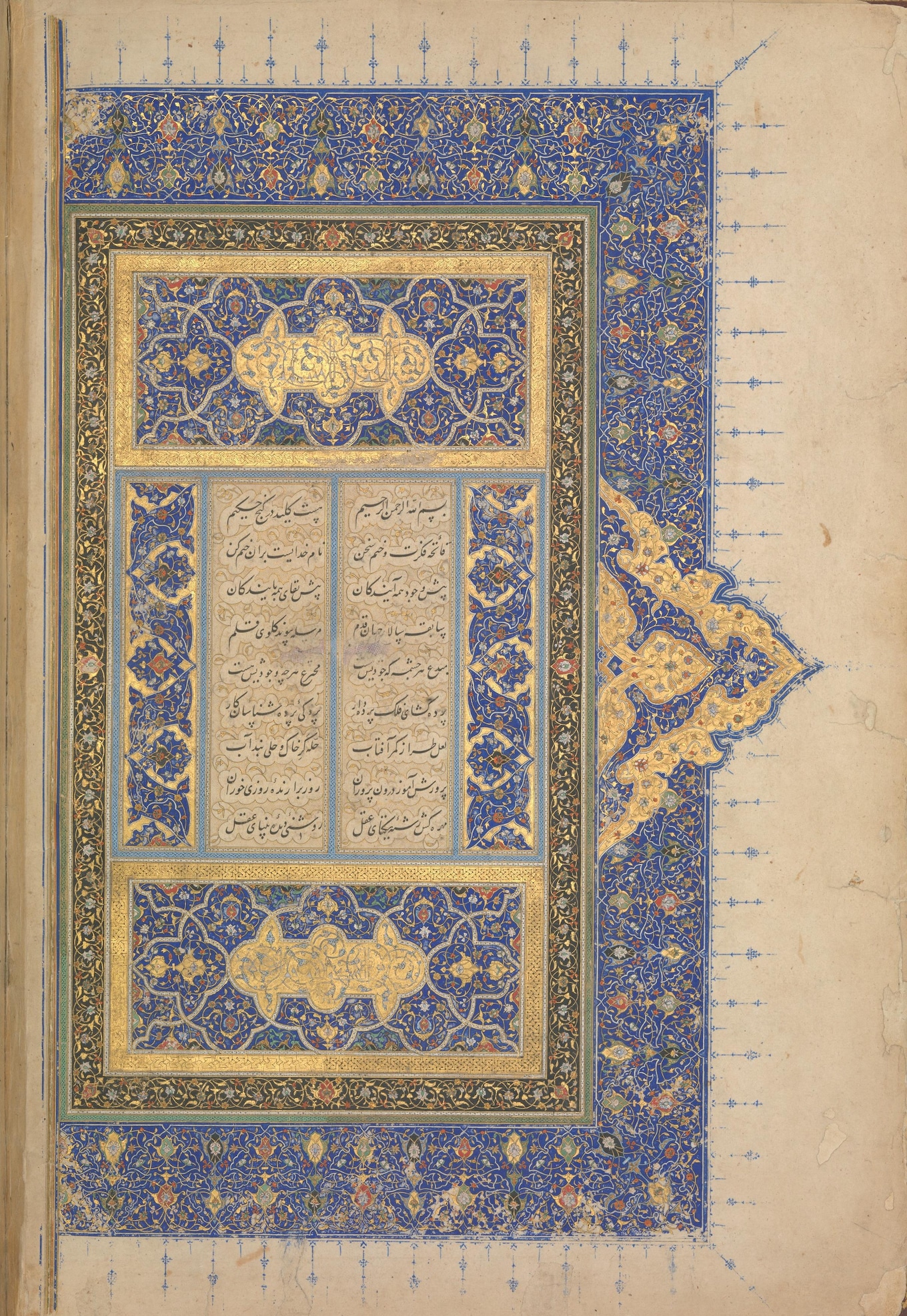

"As we did research, we looked at fabulous illumination traditions elsewhere in the world, not just Europe," explains Fallis. "I settled on some Persian illuminations and so then I thought, well, we'd better have some Persian musicians. So that's what we're combining: some Persian music with Persian illuminations, which have many similarities with Westerm ones — a great love of colour, there's also a lot of epic stories that are told in illuminations in both traditions."

Fallis invited Naghmeh Farahmand (percussion), Pejman Zahedian (Persian setar) and Demetri Petsalakis (oud) to join the Toronto Consort for the occasion. "In each half of the concert, we'll do a set, they'll do a set, and we'll try to do a set together, which is always a wonderful experiment," he says.

"There's a series of dances that come down to us in a manuscript now in the British Library, and [they're] precious because there aren't many medieval dances that got written down. About eight of them have very unusual forms and unusual scales and they do sound like Middle Eastern dances, so a lot of scholars have suggested there must have been an Arabic influence on this, or maybe Turkish, so we're going to do one of those."

This illumination comes from the 13th-century Storehouse of Mysteries by Nezami. (Metropolitan Museum)

The Toronto Consort presents Illuminations on March 2 and 3 at Trinity-St. Paul's Centre in Toronto. For mre information, head over to their website.

More to explore:

5 things you might not know about Elisa Citterio, Tafelmusik's music director

We can't stop watching this video for Ann Southam's Glass Houses No. 5